Five months into one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history, which would claim the lives of some 40 million soldiers and civilians when it was finished, something amazing happened.

On Christmas Eve 1914, roughly 100,000 troops along the Western Front laid down their arms in an unofficial truce in celebration of the holiday spirit. For an evening, they weren’t Brits, or Germans, or Russians, or French; They were brothers, laughing, playing games, exchanging gifts, praying together, and learning about each other's families back home. This brief connection transcended all barriers, from language, to culture, to battle lines.

This is the true story of a spontaneous moment which holds a special place in the history of warfare – and how the pope played an important role in its happening.

No Man’s Land

World War I warfare was defined by the brutal stalemate of trench combat, a system of deep, zigzagging trenches dug into the earth to protect soldiers from constant artillery fire and machine-gun barrages. These trenches stretched for miles across the Western Front and served as living quarters, supply routes, and defensive positions, often filled with mud, rats, disease, and the ever-present threat of sudden attack.

Separating opposing trench lines was “No Man’s Land,” a barren, shell-scarred strip of ground littered with barbed wire and the bodies of fallen soldiers. Crossing it meant near-certain danger, as troops advancing into No Man’s Land were exposed to relentless enemy fire, making even small territorial gains extraordinarily costly in lives.

The conditions were among the most horrific in the history of warfare. Life in the dank, waterlogged trenches included constant exposure to disease and injury, with ailments like trench foot rotting soldiers’ flesh from the inside out, while lifting one’s head even an inch above the trench line risked an instant death from a waiting sniper’s bullet.

Pope Makes a Plea

During the early days of the conflict, Pope Benedict XV emerged as one of the few moral voices urging restraint and calling for peace amid the carnage.

Then came December 1914. The pope reportedly made an appeal directly to the warring nations, calling for a temporary ceasefire over Christmas so soldiers could observe the holy day without bloodshed. While military leaders largely ignored his request, his plea may have echoed in the trenches.

That's when something remarkable occurred.

The Christmas Truce

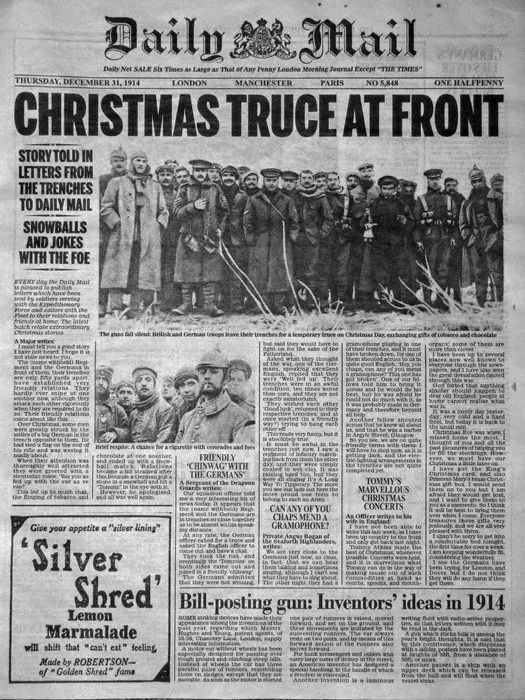

British soldiers could hardly believe their eyes when they saw the Germans place candles on their trenches and light makeshift Christmas trees. Then a German soldier began singing carols, which the Brits returned in kind.

Both sides called out “Merry Christmas” in their native tongues, and a German soldier called out to the Brits, “come over here.” A British sergeant responded, “you come half-way. I come half-way.”

Both sides were wary of a trap. But as men from the opposing armies cautiously crawled out of the trenches, no gunfire erupted. A handful of men met in the middle of No Man’s Land, and exchanged handshakes and cigarettes from their native country. Eventually, thousands emerged.

They didn't share a common language, but they found ways to communicate, including through songs and hymns. "Silent Night" was reportedly sung, along with other popular songs that could help break the language barrier.

Did the Truce Really Happen?

Is all of this too good to be true?

The short answer is: yes, the Christmas Truce absolutely happened, though perhaps not to the extent some imagine – and historians have poked holes in the warm and fuzzy story.

Reports differ on exactly what took place during the truce (and understandably so, as the front line stretched for hundreds of miles). The nationalities at play mattered, too. There was bitter animosity between the French and Germans, for example, and little evidence of fraternization between those troops. Experts say relations were even worse between the Russians and the Germans.

However, areas of the line with British and German troops had a different story. There had been no German invasion of Britain, for one. And some German soldiers had lived for a time across the channel, and many spoke English.

Indeed, plenty of first-hand sources shed light on the unlikely break in the violence (at least in some sectors).

Letters from the Front

“Here they were—the actual, practical soldiers of the German army,” wrote British machine gunner Bruce Bairnsfather. “There was not an atom of hate on either side.”

The men laughed, they played soccer, they prayed together, they traded what they had. Soldiers from one side helped bury the dead from the other side. Most could hardly believe their eyes. “Here we were laughing and chatting to men whom only a few hours before we were trying to kill!” wrote British soldier John Ferguson.

The feeling was mutual on the German side. “How marvelously wonderful, yet how strange it was,” wrote German Lieutenant Kurt Zehmisch. “Thus Christmas, the celebration of Love, managed to bring mortal enemies together as friends for a time.”

Finding Peace a Century On

More than a century later, the Christmas Truce still feels almost unbelievable – in the midst of unimaginable violence, ordinary people chose empathy over enmity and lay down their arms in fellowship, if only for a night.

However, there's a reason this truce was not repeated in later years of the war. In 1914, the worst cruelties had yet to take place. Poison gas would not be used for the first time until April 1915. And the miseries of trench warfare that would become synonymous with this conflict had yet fully materialized. After the horrors to come, there would be no friendly meetings in "No Man's Land."

And yet, in times like now, when we feel our world intensely divided, there's something soothing about the idea of humanity coming together despite it all.

In that sense, this remarkable story of 1914 stands as a quiet challenge: to remember what Christmas means at its best.

10 comments

-

There's a really great movie from 1992 called "A Midnight Clear" based on this story. Highly recommend.

-

God works in mysterious ways and at times they really don’t make Sense. But the bottom line line is God has a plan for all of us. He is in charge and in the end God wins. Merry Christmas to y’all And may the New Year bring us more of Gods blessings and unconditional love. Remember the Reason for the Season Davey🤠🐸 Somewhere in Texas 1960

-

For a few hours, humanity won.

-

Reverend Paula Copp

And that was because of Christmas! :-)

-

-

It's a shame peace cannot be repeated all over the world in this day and age 2 songs spring to mind both by John Lennon Happy Christmas war is over and Give Peace A Chance Why can't this happen over to you Putin and others. You keep threatening war on our European nations but you never do anything about it. I reckon you won't your just a big girls blouse.

-

Wonderful to see you repeat this story from so long time ago. And such a shame we won't see it repeated now.

-

Brother Peter

When Yeshua comes again!

-

-

As the default, de facto, titular temporary head, of the Secular Humanist Pantheist denomination of the Universal Life Church (in which I’ve been an ordained minister, with two DD’s since 1969) it’s pointed out to any congregation we might have, that “if” those who started wars, had to actually “fight and die” in such wars, there’d be no more wars. Wars are fought (by those actually in hand to hand combat) who know the least abut what started the war) — while those in the know, wave flags and Christian bibles at them, as they march off to war. As Nietzsche pontificated, “How good bad reasons, and band music sound, when marching off to war.”

If you get in a fight with a person in the grocery store or in front of the church, you don't call the store next door for help and you don't call the church down the block for help.

You fight your fight and both people go home.

The Men and women that declare war, should be the ones to fight the war.

You're funny Rev. Donut, the men and women that declare war are the ones that do fight the war, using the faceless, nameless, young men and women to do their dirty work.