It just got harder for members of Texas’ LGBTQ+ community to wed.

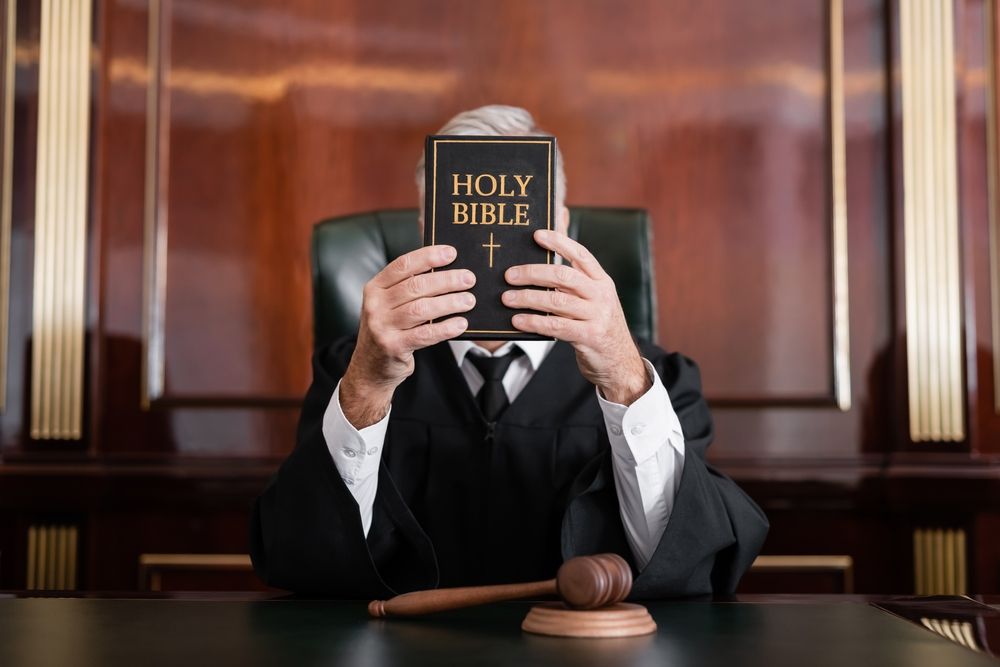

The Texas Supreme Court just quietly rewrote the rules on judicial impartiality, amending the Texas Code of Judicial Conduct to affirm that judges who refuse to marry gay couples based on their “sincerely held religious belief” are not in violation of the code and won’t face sanctions from judicial review boards.

While gay couples in LGBTQ-friendly metros like Austin or Dallas are unlikely to have trouble finding officiants, critics fear that queer Texans in smaller, more conservative towns may soon have difficulty finding someone to perform their wedding if judges can turn them down.

Legalizing Discrimination

The rule update comes courtesy of a now-withdrawn sanction against a Waco judge who refused to perform weddings for gay couples, but continued performing weddings for straight couples.

The judge, Dianne Hensley, initially refused to perform any weddings after the landmark 2015 Supreme Court decision which legalized gay marriage nationwide. However, she resumed performing straights-only weddings later in 2016. Hensley said she would “politely refer” gay couples to LGBTQ-friendly judges or officiants in the area.

The State Commission on Judicial Conduct issued a public warning to Hensley, arguing that her refusal to perform gay weddings called into question her impartiality in other cases.

Fearing similar sanctions, Brian Umphress, a county judge in Jack County, Texas who also opposes same-sex marriage on religious grounds, sued the commission.

That lawsuit prompted the Texas Supreme Court to take another look at the code, and rewrite it in a way that explicitly shields judges who cite faith-based objections to same-sex marriage.

How Was the Ruling Made?

The Texas Supreme Court has long been sympathetic to “religious liberty” defenses, often siding with those claiming their faith compels them to refuse service to the LGBTQ+ community – including in the case of Judge Hensley.

"I find it encouraging that we have no indication any same-sex couple even considered handling the situation that way. What decent person would? Judge Hensley treated them respectfully,” wrote Chief Justice Jimmy Blacklock last year. “They got married nearby. They went about their lives. Judge Hensley went back to work, her Christian conscience clean, her knees bent only to her God. Sounds like a win-win.”

To critics, that statement revealed the Court’s bias plainly: compassion for the judge’s conscience, but little for the couples she turned away.

Yet some legal watchdogs say that gay marriage’s nationwide legality means that judges either have to perform all marriages or none – and that “go somewhere else” is not a valid legal defense.

"One of the claims that I think will be made in response to litigation that is likely is that, 'well, there are other people who can perform the wedding ceremony, so you can't insist that a particular judge do it,’ stated Jason Mazzone, a law professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. "But that, of course, is not how equal protection works, and it's not how we expect government officials to operate."

Is This Legal?

The judges in these cases say that they’re guided above all by their Christian faith, and their Christian faith says that marriage is between one man and one woman. The Texas Supreme Court agrees, arguing that no one should have to violate their sincerely held religious beliefs at their place of work.

And yet LGBTQ+ advocates argue that their marriages are just as valid as any other marriage in the eyes of the law, and that it is blatantly discriminatory to perform weddings for one legal group and not another. In practice, they warn, the ruling gives a green light for government officials to deny equal treatment under the law, so long as they claim religion as the reason.

One thing’s for sure: The rights of same-sex couples to wed was once believed to be settled law. Yet as more cases challenging marriage equality make their way to the courts, that right feels anything but secure.

Friendly reminder: a judge is not the only official that can legally solemnize marriage. Anyone in Texas can become ordained with the Universal Life Church to perform legal wedding ceremonies.

Regardless, the case in Texas raises some important questions: Should personal belief allow public servants to deny equal rights under the law? What if performing weddings is part of their job?

97 comments

-

I guess you will find out the truth on judgment Day..

-

I know what the Bible says about same sex and marriage and all that goes with it, but I also know that our God is a forgiving God and he will lead you on the right path if you surrender to him and ask for forgiveness. You cannot change free will all we can do is except the choices they have made. Relay Gods word but it is their choice to make so support it and keep bringing Christ message to everyone. God Bless each and everyone reading this.

-

Poor Charles. I do sympathize with you and your misguided belief of Christ's message, however..... Christ NEVER and I do stress NEVER according to your Bible and the Holy word of God, mentioned one rebuke about Gay's, Homosexuals, or whatever they called them in the Jewish language. God and I are very good friends Charles and, he tells me that I don't need forgiveness for being what he made me as a human being! He also wants to give you a message: "GOD DON'T MAKE MISTAKES"! So you see I as a Gay man need no forgiveness from you or anyone who thinks that Christ's message is anything like you are spreading, cause what you are spreading "Ain't good News"......

-

-

Judges are supposed to uphold the law regardless of whether or not they align with their own beliefs. If they cannot or choose not to uphold the constitution of the United States, then perhaps they should seek another career choice. BTW, one of the commandment states, “Thou shalt not kill.” By how many judges have sentenced people to die? You can’t follow one rule and not the other.

-

This. This is very accurate. If they can’t marry a same sex couple who’s to say since it goes against their beliefs that they won’t be biased against them for breaking the law. They view them differently so they would still hold those same beliefs if they were to preside over trial. I feel like that they are not upholding their oath as a judge. They did not walk into a church to get wed, they went to a courthouse. This is very much a problem. If I personally were to have to face that judge I’d want them to remove themselves from handling my case as I would definitely not think they had the ability to be impartial.

-

What if those same judges refuse to marry heterosexual couples that are one Christian and one non-Christian? Would their faith prevent them from marrying them? What about mixed-race couples? Even more telling, would they perform a forced marriage on an underage child? Texas opened a bigger can of worms here.

-

-

Partial

-

The better solution is for the government (whether city, county, state, or federal) to no longer be involved in the marriage industry. In other words marriage shouldn't be a legal institution.

-

He should be given the exact same consideration as would be given to a practicing Orthodox Jew or Muslim who wanted to work as a taste tester in a bacon factory.

It's stupid to keep someone in a job they refuse to do parts of. Christianity is a choice. Sexual orientation isn't. It's not rocket science, he's being a homophobic jerk and needs to resign.

-

This is Just a way to legalize discrimination!!

If a judge can’t follow the law handed down by The US SUPREME COURT, then that judge should step down and then it won’t conflict his/her religion,

I am quite certain there must be other laws that conflict with them but they still do their job.

I say FIRE THEM!! God don’t like hate or ugly and that is ugly & hatful

-

Judges need to follow the law and be the judge for everyone. The answer is a resounding NO. They have no right to religious exemptions.

-

Agreed

-

-

Send them my way in DFW and SURROUNDING areas. I will happily do that wedding. I have no issues with performing that wedding.

Keith Ramsey Crescent Moon Weddings.

-

Praying for you people

-

Sir Lionheart

My partner and I must truly be committed Christians, as we have remained together for 20 long years despite the challenges of living with each other.

God bless him!

-

Congratulations!

Does one have to be religious to be committed to someone?

🦁❤️

-

-

Walter J. Holbrook

... and who exactly are “you people,” anyway?

-

-

The separation of church and state isn’t complicated. If you serve in government, your personal religion has no place in deciding how you treat others. Every American pays taxes and deserves the same freedoms in return. If some are denied those rights, then 1) they shouldn’t be forced to pay the same taxes, and 2) anyone whose “faith”—often Christian—prevents them from serving all Americans equally shouldn’t be in that position of public trust. Let’s not forget: Christ never turned His back on anyone.

-

Being an officiant in Texas... I'm okay with this.. I'll take that business from them.

-

-

It’s simply disgusting, but I’m not surprised at any bigotry coming from Texas.

-

Personally, I oppose same-sex marriage. I believe this is a term reserved for opposite sex couples.

The argument I continually hear is that these same-sex couples don't get the same benefits as a married couple.

Well, au contraire.

Civil Unions confer the same benefits and, even if there are any not conferred, they are easily achieved by separate legal instruments, all without being married. Any couple can receive all the legal benefits of marriage, without the instrument of marriage.

-

A Civil Union is also known as a Wedding.

-

Keith Ramsey

While that may be true in common usage, which I do not dispute, it does not hold in official documentation.

-

-

-

Gays should be allowed to marry. They have every right to be as miserable as straight couples.

-

Judges are supposed to be 'servants of the public' and that means that personal beliefs and religion should be set aside. Judges are also supposed to be impartial and uphold the law. If gay marriage is now legal, then they have no right to refuse. Period.

-

I absolutely agree.

-

-

A judge is hired by society to perform certain duties. A judge is, by the nature of his job, supposed to be impartial. If a judge will not perform his duties for all the citizens because his beliefs won't allow him to be impartial, perhaps that aspect of his job should be removed entirely. If a judge won't perform one wedding, then he should not be permitted to perform any. Of course, if he is biased against any subset of our society, then no part of his job, including ruling from the bench in a courtroom, should involve that group of people. He should not be permitted to hear any case involving, or even potentially involving, any gay person, even if that person is a police officer or other witness testifying, because his bias may not allow him to adequately hear the evidence.

-

Does having an M and crescent moon on both my palms make me a Choosen one?

-

My Partner (married spouse) and I have been married for eleven years but, have been together for 47 years. We have been discriminated against in housing, employment, and choice of church... I became ordained for the reason of helping my PLU's (people like us) to not be discriminated against in being married by someone of our own culture and community. Religion has always been and always will be the source of hatred and greed. Christ NEVER said ANYTHING about being Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, or anything one would like to call themselves. Christ NEVER condemed anyone except the adulterer whom he said "I forgive you and go and sin no more" yet, the "Christian" goes to church on sunday and that makes it ok to sin on Monday!

By discriminating against Gay marriage, it just makes the Religious zealots what they are: BIGOTS!! It won't make them Gay, it won't make them Lesbian, nor will it make them even the least bit pink on the outside, or bi. What it does make them is to look like the fools they are!!-

Rev. B.D. Rees

One may outlines three classes of biblical teaching, placing teachings on homosexuality in the second class. While some assert that Christ never addressed homosexuality, it is claimed that Christ, present in the Garden of Eden, commanded Adam and Eve to “be fruitful and multiply.”

As the Word who was with God and once was God (John 1:1), Christ also affirmed in the Gospels that marriage is indissoluble except in cases of adultery, which annuls the covenant. These statements, like others, have consistently occurred in a heterosexual, binary context.

Therefore, no additional direct statement was required, though Paul, the apostle to the nations, addressing specific needs, provided such guidance in the context of pagan worship.

The Bible, with Christ as its incarnation, does not condemn those born with impediments to marriage (eunuchs) or procreation (sterility and intersex).

Some are born eunuchs, some are made eunuchs by others, and some choose celibacy for the sake of the Kingdom of Heaven (Matthew 19:12).

For this is what the LORD says: I will bless those eunuchs who keep my Sabbath days holy and who choose to do what pleases me and commit their lives to me (Isaiah 56:4)

The Talmud, while not explicitly identifying Isaac's wife, Rebecca, as intersex, discusses individuals with ambiguous or hidden sex characteristics, using terms like tumtum to describe them, reflecting an acknowledgment of biological diversity rather than cultural constructs. In other words, the rabbis unanimously agree that Rebecca had no uterus, which makes her giving birth to twins all the more miraculous.

Although the conditions now known as LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex) are approached with compassion in Scripture. Yet, these behaviors are not exactly endorsed, as they go against the original plan in Eden, according to the Theology of the Body.

https://www.theology-of-the-body-church.co.uk/about-tob

-

Pastor Day: I am amazed at your prowess for cherry picking the Bible, you do it with such finese. However, in the New Testament I have never read one mention of Christ ever saying ANYTHING about being Homosexual or any other word that it may mean during those times. The word "HOMOSEXUAL" wasn't even coined until the 1940's. As a Gay man, I live by the precepts of the words of Christ and the Teachings of Christ. You may wish to coddle and make excuses for these BIGOTS but, I will not give them quarter to say their hateful reteric about my community!! You can talk about theology all you want, but most people are simple folk who like Christ beleive in a simple religion of "LOVING THY BROTHER AS THYSELF".... Too simple for ya? Well, it ain't for me.

-

-

-

A law to shield bigotry is really unconstitutional, but again, people do not like things shoved down their throats,which is what the woke generation is doing! Confrontations invoke fear, especially in the less educated! Bottom line is some states have a lot of people who were absent from a lot of schooling!

-

What exactly is the "woke generation"?

-

-

There are plenty of judges and others who will perform those weddings. Those wanting to force those judges to perform them are the same people who want to force a Christian baker to make their cake when there are many places to get their cakes.

It is not about rights, it is about the alphabet group wanting to force everyone to cater to them and their beliefs, thus taking away rights of others for their own agenda.-

A bakery is a business, not a religion. And businesses should not be allowed to discriminate. That said, a lawyer can refuse to take a case if s/he doesnt want to take it. I would never defend an animal abuser, for one.

-

OOOOOh Steven.... Your skirt is hiked up and your predjudice is showing!! Pull the skirt down from over your head so you can see your own agenda.... Tsk, Tsk....

-

-

Texas Won't Punish Judges Who Refuse to Perform Same-Sex Weddings but God will.

-

God won't punish them at all. What you are pushing is the lie.

-

-

I grew up during the time when the covenants of a subdivision could exclude home buyers or renters based on their skin color and religion. Business could refuse service based on skin color. Hospitals could refuse care due to a person's skin color. Whites only drinking fountains. The list went on and on.

My late husband and I were refused, when looking at renting an apartment, because my last name wasn't his, even though I had our marriage license.

And then we moved passed that. Unfortunately, it is rearing it's ugly head once again and people are coming up with all kinds of excuses as to why it is okay. It is truly sad.

-

I’ve heard it said that the divorce rate between two lesbians is quite high.

Lower down the list of divorce rates are monogamous marriages where ……..only one woman is involved. 🤭

It was suggested that the lowest rates for divorce are marriages between two men. I have absolutely no idea why that is. 🤣

Don’t you just love humor? I hope you smiled. 🤗

🦁❤️

-

This judge is on the record as having a bias against the LGBTQIA+ community. Any lawyer representing someone from that community that pulls her as a judge has just cause to dismiss the judge for that reason alone. I'm not sure how judges are assigned in the County Clerks office but if it is by rotation, she should not have the ability to decline because she doesn't "like" the couple, so this is not a reason either. If they were legally barred for any reason should be her only "out." Does the couple have the same right to dismiss a judge assigned to their "cases?" Only for bias or conflict of interest would qualify dismissing the judge (not that a couple wanting to get married in a court house would take that option). Sorry I'm rambling, but this is getting rediculous, just like everything else in this country right now.

-

This judge is a closet member of the LGBTQIA+ community.

-

Would not shock me. Those who seem to be the most active against such rights seem to have tendencies themselves. Do you think they feel it would be easier to ignore them if it was not so protected and supported to just be who they are? Certainly seems that way as so many pretenders and nay sayers seem to come out at some point or another.

-

-

-

This sort of thing used to make me feel sad but not anymore.

Appeasing the left leaves them unappeased and demanding more under penalty of anarchy, arson, subterfuge and assassination.

No. Give absolutely nothing and demand lost ground back. The left is very Russia like. Let them take land like Obama did, they'll take more land and we'll let them like Biden did.

In this way they (the left) can fight for their old trench back instead of taking my trench, which they're aiming for always.

-

SOJ,

I call BS. How is providing the same rights to exist and privleges of marriage impinging on your rights. How does it change any of your rights to marry the person you want, when you want, and where you want? They aren't asking for more. They're asking for the same, with dignity, rather than being treated as vermin.

-

They began sending kids to drag queens, sending drag queens to kids, teaching lgbtqia++ in schools, given an entire month for sex, I take corporate classes and tests so I'm aware of the 68 genders I may encounter, all whites are racist, especially straight white men, cutting off breasts and genitals of our youth, giving them pills to halt human biology on and on and on the line continues to move for more and more and more of all things I disagree with logically and spiritually.

These lgbtqia++ leftists shot a man that echoed my thoughts and beliefs. In a way, the lgbtqia++ team shot me.

Two men can't marry and two women can't marry. They can be partners and be in love but it's impossible for them to marry. Absolutely and totally impossible no matter what anyone says or does.

Enough.

-

Also, the rest of your rant isn’t factual either.

-

This is your daily reminder that Charlie Kirk was shot by a straight right-wing man. Or did you mean someone else?

-

While SOJ waders off into the tumbleweed, and since you mentioned Charlie Kirk, I think his death was just Collateral Damage perpetrated by trump to distract everyone from The Epstein Files.

-

Yes and there are videos of Charlie Kirk in the Epstein Files, right Ty?

-

-

Maureen,

It's widely known that Kirks assassin was getting busy with a dude in lipstick and pantyhose.

That ain't no straight brother bro.

-

Christians spreading their hate an intolerance others. A servant of the lord would never do that.

-

It has been alleged that Tyler Robinson was involved with a trans person. I’m withholding judgment until it’s confirmed by a reputable news source. In the meantime, I’ll drop the straight part of the equation, sure. A cis male whose orientation is unknown, then. And given the lack of evidence that anyone calling themselves Lance identifies as female, we may both be wrong.

-

Again, Maureen, you can drop the cis male talk straight away. You can drop any trans talk while you're at it.

Dude getting busy with dude=gay. The end.

-

You brought it up. Your inability to address my actual points is noted. Meanwhile, I find it hilarious that you, with all your, shall we say, strong convictions, still address someone with a uterus as “bro”.

-

-

-

Maureen Hebert Heartwood

The shooter’s sexual orientation is not confirmed, and we simply do not know.

Fact-checking indicates that his partner was transgender, which could suggest she may have male anatomy.

While not all transgender women have male anatomy, the majority do.

Therefore, assuming he was straight is speculative.

-

-

"These lgbtqia++ leftists shot a man that echoed my thoughts and beliefs. In a way, the lgbtqia++ team shot me." If you're referring to Charlie Kirk, here are a few of the racist thoughts and beliefs you apparently echo:

"If I see a Black pilot, I’m going to be like, boy, I hope he’s qualified." – The Charlie Kirk Show, 23 January 2024

"If I’m dealing with somebody in customer service who’s a moronic Black woman, I wonder is she there because of her excellence, or is she there because of affirmative action?" – The Charlie Kirk Show, 3 January 2024

"The great replacement strategy, which is well under way every single day in our southern border, is a strategy to replace white rural America with something different." – The Charlie Kirk Show, 1 March 2024

Why is Kirk's killer a reflection of all leftists to you while you have remained completely silent about the assassination of a Dem state senator, Melissa Hortman, by a right-wing extremist who loved Trump? It's not even accurate to claim Kirk's murderer is a leftist but as soon as Kirk's death was announced it was instantly the "radical left" to blame. https://www.npr.org/2025/09/18/nx-s1-5544446/charlie-kirk-suspect-shooter-motive

-

Thank you, Michael. I completely missed the reference to CK, because that theory was debunked about day two or three after the incident of his death.

-

Michael,

Yes I agree with those snippets you grabbed. Super easy to understand and super logical. When you lay down skin color as a requirement you depart from standard qualifications. Corporations can try to fill a position with a qualified minority person but ultimately will succumb to social and government pressures to just fill the spot with whatever color or gender they need to check the box off. Happens all the time if it's a rare or demanding profession. All the time.

I watched my factory fill up with illegal aliens that didn't speak a lick of English. Big time safety risk. HR chick hired them cause they work for you peanuts. The illegals replaced about 150 citizens. ICE came looking for 3 nasty ones but the lgntqia++ HR manager protected them. Can't imagine what they did for Biden ICE to come knocking, musta been bad. Nowadays ICE would have taken them no matter what and hopefully have by now. I literally watched US citizens of all races get replaced with illegals during Bidens watch.

Can we just skip the silly talk about what political side of the aisle Kirks assassin came from? The man sure didn't vote trump and neither did his boyfriend. Enough silly talk.

As far as Horman's assassin goes, find him guilty as quickly as possible then immediately get him in front a firing squad on global television with no sensitivity editing. Then do the same for kirks assassin. Let the few lunatics on the right and the entire left know assassinations end with a firing squad quick and now.

-

-

Except for educating you and making you aware that there are others out there that look and act differently, how has any of that affected you personally? As for the drag queens reading to children, so do people dressed up as Easter bunnies and Santa Claus. Drag queens are no different - just people dressing up as something else and acting a part. They are entertainers. As for the children going through gender dysphoria, as a parent, that is a right you have. They aren't doing it in schools, and they certainly not doing it withoug parental consent, so unless you gave them consent ... well you get my point. If you don't like what they teach in school you do have the option of private school or home schooling, which I highly suggest considering your complete paranoia of what is going on in our education systems. It almost equals my paranoia of what's going on in the government right now, and the thought that the country is being taken over by right wing bigots scares the (&(#$ out of me. Our whole country has become so polarized, I'm not sure that there is any peaceful way to come through this. Don't believe me, just look at what's hapening in Chicago, where the ICE thugs think they are as far above the law as the president is. Just look at Capitol Hill where the politicians are doing nothing but pointing fingers and blaming one another. When things get this far gone, neither side is right, and both of them are wrong. They all need to sit down at a table and eat a little crow (if you're old enough to get that metaphor). I'll truly pray for you SOJ. I pray for our country, and I pray that clearer and just heads prevail to lead us all out of this mess.

-

-

Patricia Ann Gross

They can love each other and enter into different forms of union.

Marriage is not solely based on feelings of love. What happens when two parents no longer love each other? Do they divide their family? We have all witnessed the consequences of such situations.

Marriage is a covenant between a biological man and a biological woman. Other arrangements, even legally recognized, are possible, as Pope Francis himself has stated.

-

Pastor George,

Because, if it has all the same rights and privileges as marriage, why call it something else? All you are doing is opening up the door for eventually making that union inferior in status and rights, and at the same time doubling the paperwork and statuses, not to mention the laws that have to align. They ARE the same thing with the same rights, obligations, and privileges. Pope Francis died last year, so you are a bit behind the times, and as a religious leader what he said has no bearing in law. It only covers one denomination in the Christian faith. There are many other religious leaders that have stated differently, in the Christian faith and others.

-

Patricia Ann Gross

I am not seeking to start an argument, nor am I willing to spend hours debating these points.

It is common knowledge when Pope Francis passed away. Notably, he was recognized for his openness toward welcoming homosexual and transgender individuals into the Church. Regardless of how many leaders exist within Christendom, the Catholic Church commands a broad audience and has significant moral authority. Consequently, its statements on such matters are closely observed. The phrase “Who am I to judge?” is well-known and may indicate that you are not fully up to date if unfamiliar with it.

Marriage predates both of us by millennia. If the discussion is about civil and equal rights, this is a practical matter tied to real life. I support legal protections and privileges for same-sex couples as did Pope Francis. However, it appears that your argument extends into a more philosophical domain, which seems to reflect your issues with religion more than anything else.

I am openly gay and in a committed relationship, so I am not unfamiliar with this specific realm of civil rights.

I will not continue this discussion. You are entitled to your opinion, as I am to mine.

-

Pastor George,

I meant no disrespect to Pope Francis, or the Catholic Church for that matter. I am quite familiar, and a lot more conservative than I come across here at times, which only shows "right and left" aren't binary. One can applaud Vatican II for addressing the schism of the Protestant Reformation (and Francis, along with John Paul II and Benedict VI were instrumental in pushing the church up to the 20th Century.by implementing the changes to the Pastoral and Admistrative Constitutions.) At the same time, we are a quarter of the way through the 21st Century, and the church has a long way to go to get here, by addressing things like protection of children within their church and acknowledging the gifts and graces of women, but then again, adapting a patriarchal heirarchy to today's cultures and technologies should not nor will not be done overnight. I was a big fan of Francis, and so far have been impressed with Leo XIV. My purpose was not to debate Catholic doctrine, but to understand why a same-sex union is different than one that is made up of people from the opposite gender. That's all. If you do not wish to continue the discussion, that's fine, but you are not the first gay person I've met who thinks that they need to be called something different when they both need the same protections and responsibilities.

The biggest concern I have with them being called something different is when gay couples decide to have children by adoption, IVF, surrogacy, or some other method. Both parents, need the exact same rights as a married heterosexual couple, so why make up a whole new category and set up the same set of rules for gay (or gender-fluid) couples? That was all I was asking. When children aren't involved or grown and the union disolves, then there are the issues of property, etc., exactly like with married couples. Before marriage equality, gay couples had to dish out tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees to make sure they had the same rights, in the event of a split, that a marriage guarantees by the marriage certificate alone.. I really don't think we need to return to that.

-

-

-

-

-

I am sorry your life is so sad, that all you have left is the Judgement of others..... Your opinion is from my perspective, absurd, and frankly ridiculous!! Judgement is never helpful or sensible....

-

Servant Of Judgement aren't you a Native American? The white folk took away took away your Gods, your land your culture and forced/brainwashed you into being a Christian.

-

I'm native American in the sense this is where I come from, yes. All humans migrated here, none are indigenous, so says science.

-

So why did you abandon your religion for the religion forced upon you by the white man?

-

So, you again are saying you don't know what you are talking about.

-

-

"Native American" as in he was born in America to a family who at some point in their lineage immigrated to America from Europe.

-

Michael Hunt what makes you so certain his lineage is from Europe? It's far more likely he is of Asian decent from Siberia. I was taught Siberia is on the Asian continent which is not Europe.

-

I'm fairly certain they've mentioned it in previous posts, or I could be confusing them with someone else. Totally possible I'm wrong, but that's what my mind first jumped to when he said, "I'm native American in the sense this is where I come from" and then makes the claim that no one is indigenous, which is just erasure of the history of the indigenous peoples living in America prior to colonization.

-

Michael Hunt I'm pretty sure in the past he's said he identifies as native American and lived or lives on a reservation.

That would make him a Lamanite who migrated from Jerusalem according to the Book of Mormon.

-

-

-

-

-

-

It's Adam and Eve,NOT ADAM AND STEVE. People and or judges have and should have the right not to perform Homosexual marriages!!!. Just my opinion and the BIBLE. REV RICHARD SALVATORE PAX

-

As everyone knows, Adam was a woman. All men begin life as females including you Richard Michael Salvatore.

-

Actually, that is not true in the eyes of the law. Life does not exist in the womb, and the fetus has no gender or sex because it is nothing but a random collection of cells, much like a cancer or a parasite. This is why abortions as birth control can exist, and why society is not charged with preventing pregnant women from endangering the unborn with dubious actions, like alcohol or drug abuse.

-

Ronaldo completely false. Where did you learn all of this incorrect information? A fetus is a parasite living off the host/mother and exhibits key traits like organization, metabolism, homeostasis, growth, adaptation, response to stimuli, cell division, and cell death. If life doesn't exist in the womb where does the a newborn come from?

It is well know ALL human life begins female. How could you not know that? This is why many males at birth are misclassified as females. Take a look in any human development text book to learn you are wrong.

-

Where did you pull this thought from? It is not true at all.

-

Ronaldo

I was under the impression that in the United States, abortion has been repealed as a federal law. Is that correct?

-

-

-

Actually, if you study it deeply enough, he did create ADAM AND STEVE.

-

Richard Michael Salvatore

That whole “Adam and Steve” catchphrase has gone the way of floppy disks—outdated, unscientific, and about as sensitive as a cactus hug to those with same-sex attraction, gender dysphoria, or intersex conditions. Time to sign up for a CPD course and join the modern era!

-

-

No religious exemptions of any kind. If you can’t do your job because of your “religious beliefs” then don’t apply for that job. Why are your beliefs any more important than mine of those of my family? They’re not.

Get over your sanctimonious, arrogant attitude. Read the Bible and ask yourself WWJD? Stop twisting His words to satisfy what you choose to believe.

-

Elizabeth Jane Erbe Wilcox

Why should we be required to follow your religious demands as if they apply to everyone? Seek out those who share your beliefs and get married within that community.

-

-

Najah Tamargo-USA

Then don't get married by a judge in Texas!!! There are alternatives!

-

Bless their hearts, I’m sure most Democrats won’t be happy with that decision.

🦁❤️

-

I'm sure most Democrats won't care, because they know they can go to the independent officiants, myself included that will have no problem doing that wedding.

There are a lot of Officiants in Texas that will do that wedding.

-

Sir Lionheart, since when and by whom were you granted the title of Sir? Have you been officially elevated to the rank of knight?

-

Thank you for your question. The title of “Sir” comes with my very grateful honorific of Lord, but you are very welcome to see me as a night of the realm on my own crusade. 🛡️⚔️🛡️

🦁❤️

-

-

-

No one would be raising a stink like this if the judge was Muslim.

-

A couple getting married in a courthouse is not wanting a religious ceremony, and a Muslim judge would probably follow the law and marry the couple, without claiming religious reasons for passing.

-

The Constitution and the ruling by the Supreme Court says that same sex marriage is legal. Therefore they are obligated to follow the law. Faith is faith and law is law. If your faith prevents you from applying the law equally, perhaps you should find another profession that doesn’t require you to do anything against your beliefs. Otherwise, you are required to perform tasks within your profession equally.

-

Agree

-

-

-

Find me a Muslim judge who has refused to perform a same-sex marriage because of their faith. If you can find a case of that happening, I'll condemn their actions the same way I condemn this Christian judge's actions.

-

Michael Hunt

They have established their own enclaves in Western countries where they implement Sharia Law.

Do you condemn this practice?

-

If there are places implementing Sharia law over the laws of their country, I do condemn that. If Sharia law is being forced on non-Muslims, I condemn that as well, just as I would if Christians were doing so.

Where are these enclaves in Western countries where Sharia law has been established? You must know of the cities where this is occurring, no?

-

Michael Hunt

In London, UK, there are several.

-

-

-

-

Texas might not. BUT GOD WILL.