History of Same Sex Marriage

Jump Ahead:

The history of same-sex marriage in western culture is intrinsically linked to the evolution of marriage in general. The institution has taken many forms in different societies since its inception.

Marriage used to be concerned solely with the transference of property. Indeed, a woman herself was seen as chattel in heterosexual marriage.

Marriage did not revolve around love or companionship. Within a legal union, sex provided a means for passing on wealth through progeny. As such, many civilizations often did not care if married parties (or more specifically, the married men) cultivated loving and/or sexual relationships outside of their legal bonds. Same-sex relationships were not terribly uncommon in older civilizations. However, due to their inability to produce offspring, they could not constitute a marriage the same way that one man and one woman, or one man with many women could.

Throughout the Middle Ages, people began placing special emphasis on procreation as Judeo-Christian beliefs became more widespread. Not only were extramarital relationships of any kind no longer tolerated, but they were suddenly deemed immoral and punishable. This included same-sex relationships, though any non-procreative sexual act was considered sodomy, even those between partners of opposite genders.

By the modern era, marriage had evolved yet again. Property and procreation were no longer considered the primary reasons for a union. The infertile and elderly could enjoy the right, along with couples that didn’t want children. With the women’s liberation movement, relationships between heterosexual couples became much more egalitarian, allowing for deviation from traditional gender roles.

Today, marriage is largely centered around love, commitment, and companionship. Same-sex couples can readily fit that definition, and that is exactly what was argued before the Supreme Court in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges that resulted in marriage equality becoming the law of the land in the United States in 2015.

Historical Same-Sex Precedence

A few Supreme Court Justices challenged the existence of societies that accepted and recognized gay unions during the Obergefell v. Hodges case. Chief Justice John Roberts declared, “Every definition that I looked up, prior to about a dozen years ago, defined marriage as a unity between a man and a woman as husband and wife,” ignoring many Biblical accounts of revered men of faith having several wives.

The late Justice Antonin Scalia asked, “But I don’t know of any - do you know of any society, prior to the Netherlands in 2001, that permitted same-sex marriage?”

While Scalia may have had a wealth of legal knowledge, he clearly didn’t do his research in this case. Indeed, there are numerous examples of same-sex marriages throughout history, though different cultures have different conceptions of “marriage” itself. Here is a brief survey from societies across the globe.

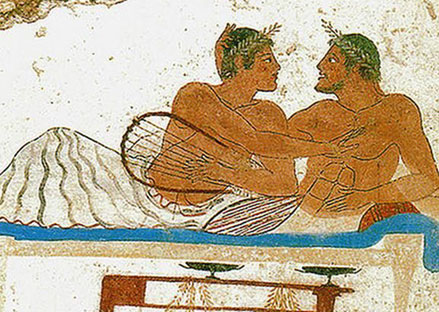

Greco-Roman

In ancient Rome, men with wealth and power sometimes married same-sex partners. It wasn’t uncommon for men and women to have sexual partners of their same respective genders, but those with influence were allowed free reign to gain societal recognition of those partnerships.

Even some Roman emperors took on husbands: Nero married a young boy in a traditional wedding ceremony where even the customs of the dowry and bridal veil were observed. About 150 years after that, Elagabalus married two men. One was a famous athlete and the other was a royal slave.

In Ancient Greek society, romance and companionship were sometimes relegated to male-male relationships. Marriage itself was often viewed as a contract and a social duty, so the close bond shared between some male couples didn’t fit the definition. Like in Roman culture, aristocratic Greek men could marry other men.

In both of these societies, there were also sexual and companionate relationships between women. However, due to their lower social status they did not enjoy the freedom to marry one another, unlike their male counterparts. We’ll see that particularly in Western culture, as women gained more and more rights, so too did same-sex couples. The idea of egalitarianism paved the way to gay marriage.

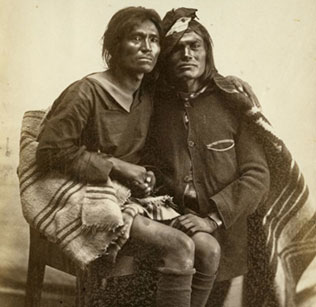

Indigenous Peoples

Many Native American tribes had a concept of what they called “two-spirited” people; those with both maleness and femaleness. While this encompassed gays and lesbians, it more broadly covered any sexual minorities, including intersexed individuals. The “two-spirited” were often respected for their unique perspectives, seen as bridging the gap between men and women.

Some tribes even permitted these individuals to marry, and in many cases that meant two people of the same gender. The Navajo was one such tribe, though in time, the sometimes violent influence of Christianity changed tribal perception and only heterosexual couples could attain a recognized union.

In parts of pre-colonial Africa, some groups allowed women to wed other women. This was an option available to widows that didn’t want to remarry a man or be absorbed into her late husband’s family. Interestingly enough, inheritance and family lineage were attached to these same-sex marriages and it was even considered normal for these women to raise children together.

The Fight at Home for Marriage Equality

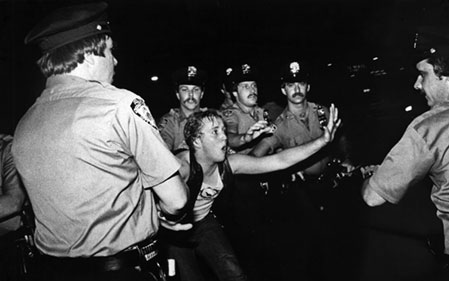

By the 19th Century, heterosexuality was seen as the default orientation and was heavily reinforced in societal norms and laws. Anti-sodomy laws took effect (though these were rarely enforced for heterosexual couples) and violence was regularly perpetuated against known gays and lesbians.

In the United States, homosexuality was viewed as a mental illness. Men and women were subjected to cruel electro-shock therapy in attempts to “cure” them and in some extreme cases, chemical castration was employed.

Gays and lesbians suffered from such a compromised social status that many had learned to hide or outright deny that fundamental aspect of their identity. They would sometimes enter into heterosexual marriages as a cover for their true orientation. This was an easy alternative because as long as a union was comprised of a man and a woman, nobody cared about it being sanctified or genuine, despite these being touted as paramount to a legal union.

1969 proved to be a turning point in the fight for gay rights, planting the seed for marriage equality in later years. Police had regularly raided a bar at the Stonewall Inn in New York City that was frequented by the LGBT community, arresting patrons without good cause. Eventually this unfair treatment reached a breaking point, and in the early hours of June 28th, violence broke out. The LGBT community rioted against the prejudiced police force. Many people recognize this moment as the birth of gay Pride. For the first time, the gay community “came out of the closet”, unafraid of the likely violence and ostracization that had compelled them to hide before. This aggressive defense of their own humanity would inspire future generations to fight for equal rights, which would include legal marriage.

Despite the lack of legal recognition, many gay and lesbian couples in the ‘60’s and ‘70’s formed lasting partnerships that were not kept secret from the public. Though the community was demonized as being promiscuous, studies found that many of these partnerships were just as stable and long-lasting as straight unions at the time. While indeed it seemed gay men had more sexual partners than the average straight person, lesbians were found to be the least promiscuous out of any group, straight or gay.

In part due to the women’s liberation movement, society’s ideas regarding traditional marital relationships started to shift. With men and women beginning to be viewed as equals, marriage was no longer seen as merely a means of procreation – it was a loving partnership. Thus, the reasons for not allowing same-sex couples to wed were quickly being whittled away.

In 1984, Berkeley, CA enacted the country’s first domestic partnership ordinance. This gave same-sex couples the ability to enjoy some of the benefits afforded to married couples. Far from comprehensive, it applied only to city employees and granted merely medical and dental insurance, as well as family leave to same-sex couples. This modest first step, however, did not go unnoticed.

Alarmed by the success of the movement, opponents of gay rights moved swiftly to action. In 1996 the US Congress penned DOMA, the Defense of Marriage Act. Signed into law by Democratic President Bill Clinton, DOMA defined marriage at the federal level as a union between a man and a woman. The bill affected a staggering 1,049 laws that determined eligibility for federal benefits, rights, or privileges. The law denied insurance benefits, social security survivors’ benefits, hospital visitation rights, bankruptcy, immigration, financial aid eligibility, and tax benefits to same-sex couples – even if they were considered married by the laws of their home state. While it did not stop states from allowing gay marriage within their borders, it prevented other states and the federal government from recognizing such unions.

Hawaii was the first to find a workaround. It became the first state to offer domestic partnership benefits to same-sex couples. However, this only applied to government employees and covered less than 60 benefits. Although the state would soon move to explicitly ban gay couples from entering into full marriages, the domestic partnership law would blaze a path that other states would soon follow.

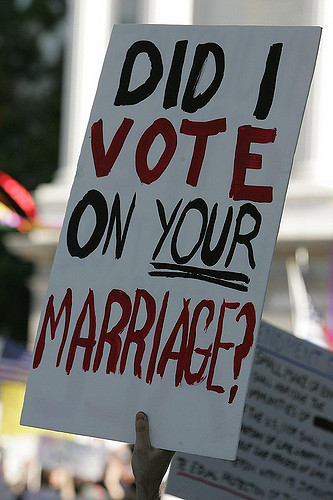

Even as “domestic partnership” was slowly spreading across the country, the next several years would see state after state vote to explicitly ban same-sex “marriage” and/or amend their state constitutions to not allow for it. Despite the campaign waged by supporters of “traditional marriage”, barriers to same-sex marriage were beginning to fall. In 2003, the Supreme Court would deal a blow to a central rationale used to deny gay couples social and legal standing.

In the case of Lawrence v. Texas, the court struck down the sodomy law in the state of Texas. It was shown that anti-sodomy laws were hardly, if ever, applied to heterosexual couples (the people that engaged in the most sodomy, a.k.a. non-procreative sex) and primarily wielded against gay couples. This was a clear violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court’s decision also invalidated all anti-sodomy laws in the 13 other states which still had them.

With these laws deemed unconstitutional, the path to marriage equality became clear; proponents would adopt the 14th Amendment strategy from Lawrence v. Texas to show that DOMA by definition was applied unevenly to target same-sex couples.

The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled in November, 2003 that “barring an individual from the protections, benefits, and obligations of civil marriage solely because that person would marry a person of the same sex violates the Massachusetts Constitution…” The argument was that if marriage was a legal union between a man and woman, and men and women were equal under the law, that barring same-sex couples from marriage was applying the law only in certain cases without a justifiable interest of the state.

“Marriage is a vital social institution,” wrote the state Chief Justice. “The exclusive commitment of two individuals to each other nurtures love and mutual support; it brings stability to our society.”

Armed with legal precedence, some clerks in California, New York, Oregon, and New Mexico began issuing marriage licenses to gay and lesbian couples within the year. The tide was beginning to turn. For the first time in the country, polls began to show growing public support for equal marriage rights.

Opponents suddenly found themselves playing defense. They moved to halt clerks from issuing licenses to same-sex couples. In Oregon, they went as far as putting a halt to all marriages, gay or straight, until the state dictated exactly who could and could not marry. In California, conservatives succeeded in legally invalidating any same-sex marriages that had been performed in the state. The nation was in a constant state of flux with respect to who could marry. Even while opponents made some gains, the house of cards was beginning to waver. The first gay weddings began taking place in Massachusetts, and in Washington DC, Congress rejected a federal ban on same-sex marriages.

California was then thrust into the national spotlight as a major battleground. Teetering back and forth between accepting and rejecting gay unions, things came to a head in 2008 with Proposition 8. Partially bankrolled by the Mormon Church, it sought to ban gay marriage in the state. Controversy arose over deliberately confusing wording as to whether the law was for or against the ban. In the end, the ban passed. However, it would not remain in effect for very long.

It was around this time that President Barack Obama instructed the Justice Department to stop enforcing DOMA, stating he believed it could not withstand scrutiny as to its constitutionality. He also personally publicly endorsed legalization. His actions appeared to give the green light to marriage equality and a small handful of states began to legalize gay marriage, including Maine, Maryland, and Washington - doing so by popular vote.

On June 26, 2013, just in time for the annual gay Pride celebration, the US Supreme Court found a key part of DOMA to be unconstitutional. This absolutely crippled the law. The court arrived at the landmark decision by way of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment; once again proving that gay rights, like all civil rights, are ingrained in the very fabric of the United States.

At the time of the filing, a majority of states still banned same-sex marriage. More than 100,000 gay couples could, however, now access the wealth of federal benefits and protections afforded by entering a legal union.

The court also found a lack of standing for defenders of California’s Proposition 8. As a consequence, the equal right to marry was affirmed in the state. In his dissent for the decision, Justice Scalia expressed concern that they had effectively provided both the argument and precedence for marriage equality on the national level. His fears would soon be realized as state after state naturally applied this rationale to legalize same-sex marriage across the country.

Legal challenges were issued to 5 states where marriage equality was still banned in 2014. On the run, opponents mounted their final defense. Their last hope was that the Supreme Court would side with their supposed right to discriminate in the name of states’ rights. When the court opted not to hear the cases, by default the last rulings on the matter were upheld, deeming the bans unconstitutional. Many legal experts viewed this as a sign that the court would soon rule in favor of marriage equality.

Victory! Free at Last

The nation was split; gay couples were able to join in marriage in some states but legally banned from doing so in states that could be just miles away. For the sake of legal consistency, it cannot be the case that both sides are correct as dictated by the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause in the 14th Amendment.

In 2015, the US Supreme Court heard the case of Obergefell v. Hodges. The case focused on the very nature of fundamental civil rights granted by the Constitution. It examined whether any harm was done by the failure to implement such rights, as well as the ever-evolving concepts of discrimination and inequality.

In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.

The decision was largely celebrated across the country. At the time of the ruling, public opinion showed a clear majority in favor of gay marriage, and like the crippling of DOMA, it came down just as many cities commemorated the riots at the Stonewall Inn in 1969 for gay Pride.

Of course, not everyone was thrilled with the landmark ruling. It dictated that all states were legally required to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. After many years of having the law on their side, opponents were now in full retreat. However, many states remained hostile to the notion of legal same-sex marriage. The county clerks in these states were faced with a decision: either grudgingly comply with the ruling, or stick by their convictions and illegally refuse to issue marriage licenses to gay couples. Many county clerks decided to comply. However, some did not – and quickly gained national attention.

Chief among them was Kim Davis, a thriced married county clerk in Kentucky who became the face of resistance to same-sex marriage. Ms. Davis, a born-again Christian, argued that her religious beliefs precluded her from issuing marriage licenses to gay couples as she believed their unions were ungodly. For months, news cameras lurked in the waiting area of that county building as Ms. Davis denied couple after couple their marriage licenses. She even went so far as to order that none of her employees issue these licenses either, given that they bore her name. Kim Davis was ultimately found in contempt of court and sentenced to five days in prison, much to the ire of the legion of social conservatives who had rallied behind her. Her movement became so powerful that she addressed huge crowds with politicians and even had an audience with the Pope.

Following Ms. Davis’s lead, other counties and states also strived to craft workarounds to protect themselves from being forced to issue marriage licenses to gay couples. Some governors threatened to sue the Federal Government while in some areas states and counties entirely stopped granting marriage licenses to anyone to avoid being charged with unequal treatment.

These efforts were all, ultimately, in vain. Marriage equality is the law of the land, but total equality is still a ways off. With the wedding fight in the past, new battles have emerged. A swath of states (largely concentrated in the South) have worked to develop “Religious Freedom” laws that protect business owners like bakers, florists, and wedding planners from being forced to provide their services to gay individuals. Meanwhile, some states have turned their sights on the transgender community, devoting their efforts to dictating who may use which public restroom.

Nonetheless, the LGBT community and its allies bask in this major victory. It affords them the ability to publicly declare their love and commitment to each other the same way that straight couples have been able to do in the United States since its founding. The gay community fought tooth and nail for decades to wear down the non-sensical opposition to same-sex marriage. Although the fight continues, this great battle was finally won.